(This post originally appeared at the Public School Notebook. We thank our attorneys at the Public Interest Law Center of Philadelphia, especially Ben Geffen and Michael Churchill, for their multi-year dedication to this effort.)

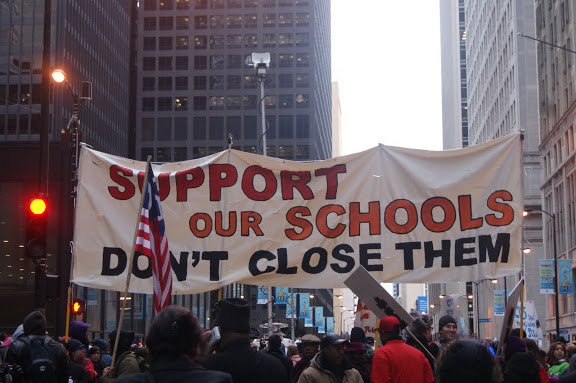

What could possibly justify the closing of Northeast High School, the largest school in the city and each year bursting at the seams? Why would anyone suggest closing four elementary schools in Olney, a neighborhood that once housed some of the most overcrowded schools in the District?

We may not find out the answers to these questions, but we know now that these were some of the ludicrous ideas proposed by the Boston Consulting Group in a long-secret 2012 report presented in a private meeting to the School Reform Commission.

BCG called for closing 88 District-managed schools, which would have displaced a conservative estimate of 22,000-31,000 students districtwide – more than triple the number of students displaced by the actual 2013 school closings. A five-year plan sought the removal and reassignment of up to 45,000 students, more than one-third of the District.

This information and more came to us after Parents United for Public Education and the Public Interest Law Center of Philadelphia won a two-and-a-half-year battle to get BCG’s list of school closings. After losing three times in official proceedings, the District this month agreed to hand over BCG’s recommendations.

More than anything, the BCG documents show deep flaws in the analysis made by multimillion-dollar paid consultants. Years later, reality also exposes how far off base BCG’s projected outcomes would be. Among some of the more troubling aspects of BCG’s school closings plan:

- Targeting 20 percent of closures – 18 schools in all – at schools which were over 90 percent full, including Lowell Elementary, Feltonville Intermediate, Barton, Hopkinson, and Frankford High schools.

- Defining low utilization at any school under 80 percent capacity. But over the last few years, between 80 and 85 percent utilization has been considered a target goal, not a delineating line for closure.

- Presuming that 100 percent of students at closed schools would automatically transfer into less-populated District schools and increase utilization rates. This proved untrue in the actual school closings process, when 24 school closures resulted in numerous students leaving the District.

- Presuming that school closings were the only means to getting District schools to increase enrollment, rather than, say, actually addressing educational improvement or opportunities.

Although some District officials tried to minimize BCG’s influence, the list clearly held weight in the final school closings outcome. BCG recommended 14 of the 26 schools – more than half – that were closed by the District in 2013.

Even today, a number of prominent groups continue to champion school closings, including mayoral candidate Lynne Abraham and Philadelphia School Partnership, one of the original funders of the BCG contract. PSP was levied fines by the Ethics Board last year for failing to comply with lobbying violations.

Parents United’s fight for this list wasn’t just about legal technicalities, although some interesting issues arose as a result. Our fight was about the importance of public transparency and dialogue on matters of grave importance to communities and taxpayers.

In 2012, the Boston Consulting Group came under intense criticism for a controversial plan that promoted school closings, massive charter expansion, and privatization of key functions within the District. Under its multimillion-dollar contract with the William Penn Foundation, BCG agreed to provide the foundation with a number of “contract deliverables,” one of which was identifying schools for closure.

In court proceedings regarding our case, the District sought to make a troubling, and fortunately unsuccessful, argument that “certain stakeholders and members of the philanthropic community” ought to have special access to information denied to the public – a move that we think is closely akin to pay-to-play.

We argued that large donors, such as former William Penn Foundation president Jeremy Nowak, had special access to school-closing documents and to District officials. AnEthics Board investigation later found that Nowak did have private meetings with District officials and reviewed and commented on draft reports.

The District held that some “members of the philanthropic community” and undefined “stakeholders” get to have a different level of access than the rest of the public. This reveals a lot about decisionmaking and voice in a state-takeover district.

It should make a difference that some of the entities that helped contribute to the Boston Consulting Group plan had board members who were real estate developers and individuals with financial and political stakes in charter school operators. These were groups that pushed hard for school closures, which rocked the District in 2012-13, forcing 7,000 children to crowd into schools that today are worse off than the ones they had attended. A number of the properties were then fast-tracked for sale.

We know that mass school closings didn’t improve the District’s finances. They didn’t stop the loss of nearly 4,000 jobs just a few months later. They didn’t buy us any good will from the state legislature. And most important, they didn’t improve the academic opportunities for students in schools targeted for closure or for those in the rest of the District.

As teacher Andrew Saltz wrote in this great piece, when his school went through the closings process:

“They wouldn’t have to walk through gang territory or take a 70-minute bus ride just to stay in their ROTC program. … Not a single person involved in the process, from the Boston Consulting Group that wrote the closure plan to the William Penn Foundation that funded it to the School Reform Commission that voted on it — none of them are accountable to the people who are suffering the consequences.”

For Parents United, this is a lasting lesson about the importance of public decision-making and voice. It’s a lasting reason why money shouldn’t buy access in lieu of democratic processes.

And it’s why we will keep fighting for a public voice in our schools.

Read more about our fight against massive and reckless school closings here.

Thank you for your vigilant work in this and other areas. Apparently Democracy isn’t guaranteed, but, rather, is perpetually subverted by well informed, well funded, and well positioned “stakeholders” whose agendas somehow slant the game board so that the money rolls in their direction.

As a teacher in one of the schools that absorbed half the students from the Pratt Elementary school closing, I can tell you first-hand that students and staff here have not experienced any increase in support or resources, but instead are challenged to do more with less.

I was wondering:

What are the thoughts/positions of Parents United for Public Education regarding the proposal to disband the SRC and create some kind of locally controlled school board?

Hi Jonathan! Thanks for writing and especially about sharing the impact of the Pratt closing.

A vast majority of us support a locally elected school board. But just as important, we want to see a fair funding formula for schools AND the elimination of emergency receivership. Emergency receivership coupled with inadequate funding has only meant that Districts like Chester-Upland may transfer from state to local control then continue on an unfunded dysfunctional path toward emergency receivership.

Thanks for you reply. What you say makes sense. The PFT is trying to get an idea of what teachers would like. My sense is that most teachers, including myself, are not well informed about the implications of a locally elected, mayoral appointed, or state/city hybrid model for district governance. It’s my understanding that Philadelphia has not had a locally elected school board for over a century. I wonder why.

As you say, fair funding is of equal (if not greater) importance.